In America we tend to think of Europe, with its unions, high taxes, and (relatively) generous safety net, as well to our left, often noting that right-leaning politicians there are committed (or at least resolved) to more progressive policies than our nominal Democrats. For instance, take a look at Thomas Geoghegan's paean to the workers' paradise that is Germany: Were You Born on the Wrong Continent? How the European Model Can Help You Get a Life -- and follow that up with Geoghegan's Only One Thing Can Save Us: Why America Needs a New Kind of Labor Movement, which argues that America's economy needs European-style labor unions to finally crawl out of the morass the Great Recession, on top of thirty years of union-busting, plunged us into. Given this, it's disconcerting that Europe as a whole has done an even poorer job than the US has in recovering from 2008, and it takes some careful analysis to understand why.

Economists like Paul Krugman were quick to blame the Euro, and there can be no doubt now that the idea of having a common currency without a common commitment to the economic vitality of the entire region is a recipe for disaster. Since its inception, the Euro has been tightly controlled by its (mostly German) central bankers, but it was the 2008 crash which made the problems clear. Before crash, the Euro built up both sides, encouraging the north to loan money to the south and fueling a real estate bubble in the latter. After, both sides were hit with depression, but the debt burden turned them against each other. As lenders, the north (mostly Germany) wanted to hold the value of the Euro firm, while the debt-hampered south needed debt relief and restructuring, things normally done by inflating the currency. What followed wasn't a compromise. The central bankers held firm, oblivious to the pain they caused in the south.

Similar problems afflicted Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Ireland, but were worse in Greece, partly because Greece had played a rather loose game with EU debt rules in the past (Michael Lewis covers this in Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World). But what has made the situation in Greece much worse has been a brutal austerity program insisted on by the central bankers -- one suspects as much intended as punishment as reassurance that the debts would be paid. So far the results are a super-depressed economy with over 25% unemployment, the election of an anti-austerity leftist political party (Syriza), a banking crisis, an increasing polarization between Greece and Germany (to the extent that Greeks have started to bring up the issue of reparations for German WWII atrocities). Indeed, since Syriza was elected, the demands of the central bankers seem to have focused as much on undoing the election results as permanently burdening the Greek economy.

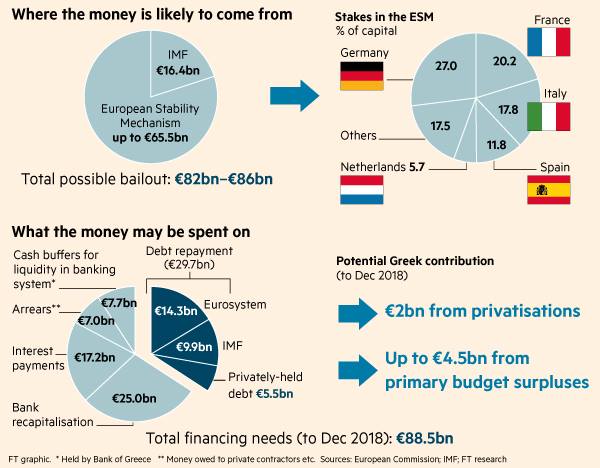

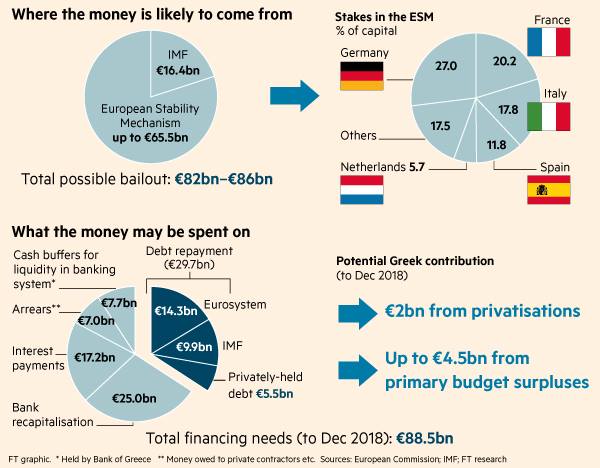

Unfortunately, it now appears that the Syriza government has capitulated to a "$94 billion bailout package" that the Greek voters decisely rejected just a week ago. (For some details, see the image below. It appears that the real beneficiaries of the "bailout" are the lending banks, that the Greek government will remain saddled with crippling debt indefinitely, and that the Greek government will be stripped of assets and prohibited from doing anything that might stimulate economic recovery.)

I say "unfortunately" because I see Greece as the first major breakpoint in what will become a worldwide struggle against debt. As you know, inequality of income and wealth has been increasing all around the world since the 1970s. There are lots of reasons for that, notably globalization which has allowed capital to seek greater profits while arbitraging wages, the practice of virtually all governments of managing their currencies through the banks, and the ever-increasing corruption of democratic institutions in favor of the oligarchy. By the 1990s, inequality had grown to the point where it was starting to suppress demand for products and services. But rather than increasing wages to stimulate demand, the problem was temporarily avoided by opening up access to debt. The idea behind debt, after all, was to preserve the power of the rich even while they let you (temporarily) sample a bit more wealth. The 2008 crash occurred when the debt overhang became insupportable, but rather than solving the problem by reducing the excess debt (by writing it down, or inflating it away, or otherwise making it easier to repay) the political system, including most of the nominal left, conspired to defend (both ideologically and through massive bailouts) the oligarchy. (See Philip Mirowski's Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown.)

As Steve Fraser documented (see The Age of Aquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power), it wasn't long after the abolition of slavery in the US that workers started referring to the "free labor" system as "wage slavery." The idea was that the conditions of wage work offered workers little real freedom. Similarly, debt constricts freedom. For individuals this may just be a matter of binding you to rat race with little hope of ever breaking free. But as Greece shows, whole nations can be reduced to debt slavery, their democratic will put aside, their people's hopes and prospects put on hold while their creditors pick their pockets. If this seems too harsh, consider this description from Alex Gourevitch:

The draft of the agreement between the Greeks and the Eurogroup is out and, as everyone has noticed, it is not just an act of revenge -- it is a piece of legislative torture. It contains old demands, like pension reductions and higher taxes to fund primary surpluses, as well as new demands, like a reduction in the power of unions and a massive privatization of state assets using a separate fund controlled by Greece but monitored by the European Union's institutions.

In fact the document asks for a massive legislative program touching on every aspect of Greek economic life -- tax policy, product regulation, labor markets, state-owned assets, the financial sector, shipping, budget surpluses, pensions, and so on. This legislation is demanded within the next few weeks. Such a package is the kind of thing one sees during or just after wartime, not as the product of democratically negotiated decisions.

Let's remember that the program on which Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and the Eurogroup agreed is something asked of a country that has already experienced a very severe depression, implemented a number of constraints requested by creditors, and has a 25 percent unemployment rate and a banking crisis. What is the point of torturing a victim whose will is already broken? To destroy all opposition. [ . . . ]

Note not just the scope of the Eurogroup's demands but the molecular level of detail with which they lay out demands. For instance, as part of their package of "ambitious product market reforms," they insist on changes in "Sunday trade, sales periods, pharmacy ownership, milk and bakeries, except over-the-counter pharmaceutical products, which will be implemented in a next step, as well as for the opening of macro-critical closed professions (e.g. ferry transportation)."

Then there are the new demands, like "rigorous reviews and modernization of collective bargaining [and] industrial action," which is Eurospeak for rubbing out labor rights. Other demands make it clear that these decisions are not only extensive and fine-grained, but designed as much as possible to remove responsibility and control from the Greek people and their government. [ . . . ]

Most telling of all, "The government needs to consult and agree with the Institutions on all draft legislation in relevant areas with adequate time before submitting it for public consultation or to Parliament." That is to say, on every above-named area of reform -- from tax policy to labor markets -- the government must consult first with its European managers. [ . . . ]

There is no guarantee the money is forthcoming. In other words, the Eurogroup retains maximum discretion to decide that Greece has failed to meet any of the impossible demands made upon it, while the Greeks possess no similar ability to hold the Europeans to account for their failures.

This kind of control through debt isn't new: it's reminiscent of similar "austerity" programs imposed on many third world countries. But those deals fell out of fashion after Argentine bucked the IMF in 2000, and the IMF has since appeared to be more sensitive to the underlying welfare of the countries it previously victimized. (The IMF has even been relatively sane regarding Greece: see Paul Krugman: An Unsustainable Position). Still, one might have expected Greece to catch a break: as a member of the EU, Greece might reasonably have expected special consideration to keep its economy functioning within European norms. It also might have expected other Eurozone members to help keep it in the zone rather than pushing it out. The decision to make an example out of Greece suggests that the powers that be fear that Greece may not be an isolated example: sooner or later others are going to revolt against the yoke of their debts.

In the meantime, of course, it could just be that the creditors are feeling invincible. In Europe, the chief evidence for this is the lacklustre ambivalence of the so-called left: why, for instance, is there so little evident solidarity between labor in the rich north and the depressed south? France has a "socialist" prime minister who seems more comfortable as the caretaker of neoliberalism than as its undertaker. The latest left-party governments in Germany and the UK have been major embarrassments, unable even to turn the right's austerity fads into meaningful political gains. I cited Fraser's book on the loss of class consciousness in America, but clearly a comparable book could be written about Europe, even if some of the particulars differ.

I've been hoping that Syriza will hold firm in rejecting the central bankers' demands, even to the point of resurrecting their own currency (and hopefully burying the dread term "Grexit" -- how sophomoric can you get?). Even if euro exit was intended as punishment (which appears to be the case in promulgating such onerous terms), and even if it hurt plenty, it would sever the bonds strangling the economy and paralyzing the party's efforts to rebuild a more just nation. It wouldn't be easy, but Greece could then rebound, and with it we might discover a viable left alternative. (Iceland was the country in worst shape after the 2008 crash, but having its own currency it devalued, stiffed its creditors, and rebounded remarkably fast.) More countries could join Greece, and/or a broader struggle -- and/or greater calamities -- might force the EU to reform. But at least there would be an alternative to the oligarchs' desperate struggle to control everything.

I have an unread book on a shelf somewhere whose title begins Another World Is Possible -- a concept that lots of people seem to have a lot of trouble grasping. (It's by Susan George, from 2004, and the title continues, rather ominously, If . . . , to remind us that activism, not just imagination, is required.)

Some more interesting links:

Chris Arnade: Blame the Banks:

The launch of the common European currency, the euro, ushered in a period of European financial confidence, and we on Wall Street started to take advantage of another willing fool: European banks. More precisely northern European banks.

From '02 until the financial crisis in '08, Wall Street shoved as much toxic waste down those banks' throats as they could handle. It wasn't hard. Like the Japanese customers before them, the European banks were hell bent on indiscriminately buying assets from all over the globe. [ . . . ]

The European banks weren't lending recklessly to only the U.S. They were also aggressively lending within Europe, including to the governments of Spain, Portugal, and Greece.

In 2008, when the U.S. housing market collapsed, the European banks lost big. They mostly absorbed those losses and focused their attention on Europe, where they kept lending to governments -- meaning buying those countries' debt -- even though that was looking like an increasingly foolish thing to do: Many of the southern countries were starting to show worrying signs.

By 2010 one of those countries -- Greece -- could no longer pay its bills. Over the prior decade Greece had built up massive debt, a result of too many people buying too many things, too few Greeks paying too few taxes, and too many promises made by too many corrupt politicians, all wrapped in questionable accounting. Yet despite clear problems, bankers had been eagerly lending to Greece all along.

That 2010 Greek crisis was temporarily muzzled by an international bailout, which imposed on Greece severe spending constraints. This bailout gave Greece no debt relief, instead lending them more money to help pay off their old loans, allowing the banks to walk away with few losses. It was a bailout of the banks in everything but name.

Because the 2010 "relief" package only added to Greece's burdens, another "relief" package became necessary in 2012, and again in 2015. The only things that will Greece to dig out of its hole are some form of debt relief and the freedom to stimulate the economy: the latter, even without the austerity requirements, is precluded by the euro.

Josh Barro: The IMF Is Telling Europe the Euro Doesn't Work:

The I.M.F. memo amounts to an admission that the eurozone cannot work in its current form. It lays out three options for achieving Greek debt sustainability, all of which are tantamount to a fiscal union, an arrangement through which wealthier countries would make payments to support the Greek economy. Not coincidentally, this is the solution many economists have been telling European officials is the only way to save the euro -- and which northern European countries have been resisting because it is so costly.

Anooja Debnath: Lose-Lose: Greece Leaving Euro Seen Costlier Than Write-Off: By about 100 billion Euros if you're counting, a stiff price to make a point.

Jonathan Hopkin: Greek Parliament passes debt agreement, but European democracy is on its knees: this loss of democratic to special interest powers over economic affairs is precisely what is so ominous about arrangements like TPP:

If the reforms fail, who will be held accountable? Certainly not the people who designed them. Whatever happens, Greece can be accused of not going far enough, as indeed it has over fiscal policy, despite undergoing a much greater fiscal squeeze than any other member state.

The destruction of democratic decision-making in Greece may indeed be the result of the country's own past mistakes, but even so, it takes the European Union to an entirely new scenario, in which economic policy is now the exclusive preserve of EU officials who have no direct interest in the success of the Greek economy.

Paul Krugman: Roach Motel Economics:

So we have learned that the euro is a Roach Motel -- once you go in, you can never get out. And once inside you are at the mercy of those who can pull your financing and crash your banking system unless you toe the line.

I and many others have had a lot to say about the politics of this reality. But let me say a word about the economic implications for the euro area as a whole -- which are basically that Europe has created a system that treats surplus and deficit countries asymmetrically, even more than the classical gold standard, and leads to a severe deflationary bias.

This is true both for fiscal issues and for balance of payments issues. Debtors are forced into draconian austerity, while creditors face no pressure to reflate; economic crisis, which should be met with expansionary policy, instead leads to contraction because of this asymmetry. Meanwhile, countries that find themselves overvalued are forced to deflate in an effort to regain competitiveness, while undervalued counties face no pressure to help out with a higher inflation rate -- so at times of major misalignment, when moderate inflation can help, the overall effect is declining inflation and maybe even deflation.

Marina Prentoulis: After Greece's defeat, we need a new European movement against austerity: Well, of course, but the examples are still coming from the southern fringe, not from the wealthier nations which have acceded power to their financial elites.