Latest

2024

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2023

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2022

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2021

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2020

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2019

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2018

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2017

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2016

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2015

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2014

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2013

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2012

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2011

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2010

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2009

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2008

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2007

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2006

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2005

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2004

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2003

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2002

Dec

Nov

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Jan

2001

Dec

Oct

Sep

Aug

Jul

Jun

May

Apr

Mar

Feb

Thursday, November 29, 2007

The Putz of Peace

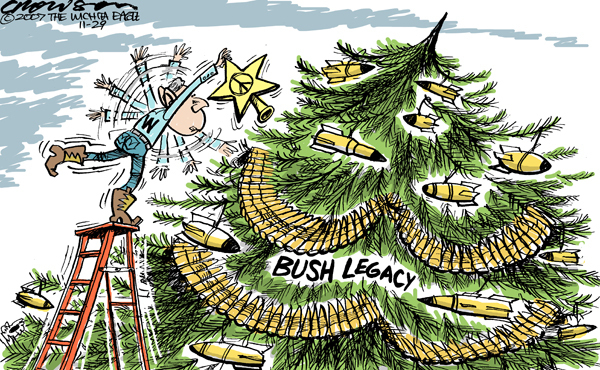

Wichita Eagle editorial cartoonist Richard Crowson weighed in on Bush at Annapolis today:

I don't really get the "Wanted: Abominable snow monster" title, but one thing is becoming clear: Bush has entered his endgame now. He is thinking not just about how history will view him, which is a sort of vanity many public figures share, but how to lock in and make permanent the changes he has attained. He has, for instance, announced that he is working on an "enduring relationship" deal with Iraqi Prime Minister Maliki, even though most of the Democrat contenders likely to replace him, and a big majority of the American people, want nothing of the sort. The announced schedule for his Annapolis initiative envisions an Israeli-Palestinian pact by the end of his term -- another little present to bestow on whoever wins the opportunity to clean up his messes. He's long campaigned for making his tax cuts permanent. His numerous executive orders are often intended to outlive his administration, and we can expect many more in his waning days -- not to mention a raft of pardons for all involved in an administration that wallows in criminality.

It's been clear all along that whoever followed Bush would have to wind up reversing almost everything he's done. There's certainly never been an administration that's so consistently, so persistently, taken wrong turns into blind alleys. Still, the waning months of his administration present still more terrifying opportunities for further misadventure -- not least because Bush appears to be going down to defeat, he's likely to see this as the last chance for quite a while to make use of presidential power.

The Crowson cartoon is a propos not only in that Bush's legacy has been one of belligerence run amok but also in the sense that he only ever conceives of peace as the fruit of victory. For him, peace only occurs when your enemies submit to your overwhelming force. That may be what he intends for Annapolis, but Israel has always enjoyed overwhelming force against Palestinians and never gotten their desired measure of submission and acquiescence from it. The dominance Bush seeks may achieve a truce here or there, but it's no substitute for justice, which can only be achieved by acknowledging equal rights for all. That is the one thing the hard core right can never concede, and that is why Bush always finds himself dumbfounded, staring up blind alleys.

But the other thing about Crowson's cartoon is how puny and inept Bush looks in comparison to the mountain of belligerence he has created. Even if he manages to cut his deals with Maliki in Iraq and Olmert and Abbas in Israel/Palestine he will have bargained with people who barely represent their constituencies, who have limited flexibility in what they can agree to and most of all in what they can deliver. Bush is in no better shape: he is not only a lame duck, he has lost Congress and has the worst popular approval ratings in history. That's not enough to keep him from being dangerous, but it's a weak hand for dealing with his problems.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Music: Current count 13831 [13813] rated (+18), 809 [826] unrated (-16). Last week was almost a total wash out. Worked on the basement Monday and Tuesday, building a platform for a new washing machine. Thursday was Thanksgiving, the start of a long weekend, full of various functions. Recycled Goods is due, so what little time I had was spent on it. And there I'm trying to get the big boxes out in time for Xmas, so the body count really slipped. Also had a big chunk of website work to do for Christgau, so I've been super-bogged down, with little to show for it. Feel lousy, too. Also I got essentially none of my incoming paperwork done, so the unrated dip is temporary.

- Bob Dylan: Dylan (1962-2006 [2007], Columbia/Legacy, 3CD): Having grown up with Dylan, following his albums one by one as they appeared, watching his stock rise and fall and rise again, noting how my own interest waxed and waned, I've never had much use for his frequent compilations. His early style evolved so furiously that the 1967 Bob Dylan's Greatest Hits, each song including the bait exclusive "Positively 4th Street" individually brilliant, was jarringly at odds with itself. He has a dozen or so key albums best owned whole, each coherent and richly detailed. Compilations try to compete by rescuing the better songs from the weaker albums. Dylan had a slack period, roughly from 1975-90, but even there choice pickings like "Precious Angel" rarely stand up to the competition. Still, this isn't a bad time for a career-spanning retrospective. His three latest albums, from 1997's Time Out of Mind, are as accomplished, albeit far less prophetic, as those from his 1960s prime. And we can trace his renewal back further -- I figure the icebreaker was 1988's The Traveling Wilburys, a masquerade that fooled no one. Moreover, most folks have a lot of catching up to do. I suppose they are who this is for. The three discs break out reasonably: 1962-67, 1969-85, 1986-2006. They pull 51 songs from 33 albums, including several compilations and two soundtracks. It's a fair sampling, missing much, trying to make a modest case for the slack period -- but note that when they cut the set down to a single disc they jump from 1976 to 1997. When I saw Dylan a few years ago, I noted that the crowd was evenly divided between folks more/less my age and the teenaged children they dragged with them. This is for the kids. A-

- Bob Dylan: Dylan (1963-2006 [2007], Columbia/Legacy): This single-disc not-so-cheapie is for the little kids, or if you want to hedge your gift-giving bets; it skips everything from "Hurricane" in 1976 to "Make You Feel My Love" in 1997, and saves "Forever Young" for the closer, as if it sums anything up -- it was more like the start of several decades of confusion, but the little kids don't need to know that much yet. A [estimate based on 3-CD superset]

- Van Morrison: The Best of Van Morrison: Volume 3 (1992-2005 [2007], Exile/Manhattan, 2CD): The first volume suffered from an embarrassment of riches (if you call that suffering), and the second one worked too hard to redeem the weaker albums at the end of Morrison's Polydor string, or perhaps didn't mind throwing some cold water on an artist who had taken his business elsewhere. This sums up a decade-plus of self-proclaimed exile. He turned out solid-plus albums -- only Down the Road stands with his greatest work, but few if any disappointed -- and he worked hard, networking with old Brit stars (Lonnie Donegan, Georgie Fame, Tom Jones), blues legends (John Lee Hooker, Junior Wells, BB King), and other voices almost as singular as his own (Carl Perkins, Ray Charles, Bobby Bland). It's hard to imagine anyone else fitting in yet standing out so effortlessly. Picking obscure tracks from tributes and soundtracks, unveiling two previously unreleaseds that make you wonder how'd they been missed, and documenting each detail faithfully, this is a rare compilation that resolves any doubts about the period. A

- Stevie Ray Vaughan & Friends: Solos, Sessions & Encores (1978-88 [2007], Epic/Legacy): I.e., the sort of thing you find at the bottom of the barrell; sessions with Marcia Ball and (especially) David Bowie, while producing good songs, seem especially pointless; more true to form are the live jousts with black bluesmen, where Vaughan tried to show he belonged and often brought down the house. B

Jazz Prospecting (CG #15, Part 9)

OK, let's forget about last week. I wasn't able to work on jazz prospecting at all. I knew it was going to be bad with Thanksgiving, the long weekend, and the impending Recycled Goods deadline. On top of that, I had to spend a couple of days doing emergency carpentry, plumbing, etc., so I barely got a chance to listen. And I figure it's do-or-die time for the big Recycled box sets, so a lot of the time I did manage to spend hasn't shown up in my counts yet. The biggest by far is Allen Lowe's That Devilin' Tune, 36-CDs of vintage jazz history, replete with a 312-page book that I'm only about 1/3 of the way through. I'm having trouble getting off the fence on the Miles Davis box too. And there are other non-jazz things pending -- as I'm writing this I'm playing the Luther Vandross box. I thought about just punting this week, but don't see any point in holding the Blue Note reissues back. Next week will be better, but first I have to decide what to do with Recycled Goods. December's column will be the 50th, with more than 2100 records covered. It takes a lot of time and I'm not getting much out of it any more -- even the records have been drying up, although I really haven't had the time to put much effort into digging them up. Maybe a change of venue would help? I've thought about something more blog-like, in shorter, more frequent chunks. Also been thinking about building a reference-oriented site, which is what the consumer guiding has always been aiming at. In any case, I should get through this tight spot sooner or later next week. Not that far away from closing out this Jazz Consumer Guide. Just have to get to the beginning of the end.

Grant Green: The Latin Bit (1961 [2007], Blue Note): The latin percussion is professional enough -- Johnny Acea on piano, Willie Bobo on drums, Carlos "Patato" Valdes on congas, Garvin Masseaux on chekere -- but they can't inspire Green to break out of his usual groove. Two later cuts with Ike Quebec on tenor sax and Sonny Clark on piano work better, with the chekere gone and the congas reduced to atmosphere. B

Ike Quebec: Bossa Nova Soul Samba (1962 [2007], Blue Note): Or something sorta like that, although Soul is the only part of that title Quebec's all that conversant with; the rhythm team leans Hispanic rather than Brazilian, and may have meant the lazy riddims as satire, but the tenor saxophonist took them as an excuse for a shmoozy ballads album, which is his forté. B+(**)

Walter Davis Jr.: Davis Cup (1959 [2007], Blue Note): A minor hard bop pianist, worked with Dizzy Gillespie, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Art Blakey, Archie Shepp, Bobby Watson, a few others. This quintet was his only album on Blue Note, or for that matter under his own name until 1977. He wrote all the pieces, but he doesn't get much piano space. The album is dominated by Byrd, with McLean present but usually laying back. B

Lee Morgan: Indeed! (1956 [2007], Blue Note): The 18-year-old trumpet whiz's first studio experience, cut one day before the Hank Mobley session that Savoy rushed into print as Introducing Lee Morgan, this is as interesting for the presence of rarely-recorded Clarence Sharpe on alto sax and the way Horace Silver's piano jumps out at you; Morgan still had a ways to go, but the excitement around him was already palpable. B+(***)

Lee Morgan: Volume 2: Sextet (1956 [2007], Blue Note): Less than a month after Indeed!, Morgan is sounding even more confident in a larger, more daunting group featuring Hank Mobley on tenor sax and little known Kenny Rodgers on alto sax, with Horace Silver again providing his inexorable bounce. B+(***)

Lee Morgan: Volume 3 (1957 [2007], Blue Note): Still 18, at the helm of a subtler, more sophisticated sextet, and even more clearly the star, despite the estimable talent around him -- saxophonists Benny Golson and Gigi Gryce, pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Charlie Persip. Golson wrote the whole program, spreading out the complexity, while Kelly holds it all together. B+(**)

Lee Morgan: Candy (1957 [2007], Blue Note): Still in his teens, but at last out front alone, leading a quartet with the redoubtable Sonny Clark on piano, running through a mix of standards, including a couple he reclaims from the pop/r&b charts -- "Candy" and "Personality"; he's bursting with energy and ideas, still finding himself, but completely in control. A-

Baby Face Willette: Face to Face (1961 [2007], Blue Note): Organ man, church schooled, natch, cut two albums in 1961 with guitarist Grant Green and drummer Ben Dixon, then for all intents and purposes disappeared; this one adds Fred Jackson on tenor sax, whose skill set is summed up in the title of his one album, Hootin' 'N Tootin'; still, it's hard not to enjoy their gutbucket soul jazz. B+(***)

Paul Chambers: Bass on Top (1957 [2007], Blue Note): One of the top bassists of the era -- AMG's credits run to seven pages, all the more amazing given that he was just 33 when he died, although I figure 1/2 to 2/3 of those are dupes for compilations. Although he did a handful of albums as a leader, this is exceptional in its focus on the bass -- or at least it starts that way, as guitarist Kenny Burrell later moves to the fore. B

Lou Donaldson: Gravy Train (1961 [2007], Blue Note): An alto saxophonist, Donaldson got a reputation early in the 1950s as a Charlie Parker imitator, but it's hard to hear the influence, especially by the early 1960s when his easy-flowing blues style fit snugly into the soul jazz milieu. The temptation to put him down as derivative may be because he never showed any big ambitions. He was content to knock off dozens of clean toned, easy grooving albums, popular enough that Blue Note kept him employed from 1952 to 1974. This one makes the most of his limits. Two originals are small ideas worked out comfortably. The covers carry stronger melodies, which he renders with little elaboration but uncommon elegance. Herman Foster's piano is crisper than the usual organs, while Alec Dorsey's congas lighten and loosen the beat. A-

Count Basie: Basie at Birdland (1961 [2007], Roulette Jazz): This is about where Basie's "Second Testament" (as they put it here) band starts to slip, but they can still kick the old songbook into high orbit, the section work is atomic, a key tenor sax solo (Budd Johnson?) is much further out than expected, and Jon Hendricks mumbles his Clark Terry impression on "Whirly Bird." Nearly double the length of the original LP, the extra weight suits them. A-

Thad Jones: The Magnificent Thad Jones (1956 [2007], Blue Note): The title strikes me as a play on Jones' debut album on Debut, The Fabulous Thad Jones -- among other things it implies continued growth. The slowest great trumpet player of his generation, Jones never dazzled you with his chops, but he had an uncanny knack for finding right places for his notes, and at his moderate pace you get to savor the full beauty of the instrument. Ends with a graceful non-LP duet with guitarist Kenny Burrell. A-

No final grades/notes this week on records put back for further listening the first time around.

Unpacking:

Got some things, but didn't get them logged this week.

Sunday, November 25, 2007

Weekend Roundup

The notion that the Surge has succeeded in securing Iraq seems to have become dogma. The NY Times had a note on how Clinton and Obama are falling in line -- they seem to be as adept at falling for the party line as the media. Still, the "good news" is full of caveats. In particular, the political reforms Washington favors, ostensibly aimed at reconciling Sunnis and Shiites (not to mention Iraqis and multinational oil companies) have gone nowhere. Of course, security is a relative matter. We're still not seeing US reporters wandering the markets unguarded like they could in the early months of the occupation in 2003. Quite simply, Iraq is still the most dangerous place in the world. If it's quieter now, that's most likely because it's in everyone's interest to cool it and bide one's time. Bush's days are counting down, and the best he can hope for is to hang on long enough to pin the defeat on his successors, presumably the Democrats. As for the Iraqis, well, who wants to be the last to die when there's light at the end of the tunnel?

Joseph E. Stiglitz: The Economic Consequences of Mr. Bush. While this seems like a fair summary of what Bush's policies have done to the economy, it doesn't have the rigor of Stiglitz's estimates of Iraq war costs -- which he pegged at between $1-2 billion a year-plus before Congress came up with a $1.5 billion tab. Although the slumping economy was still a big issue in the 2004 elections, the post-election growth spurt has sufficed to get Bush off the hook, at least as far as one can tell from the media. Stiglitz touches most of the bases, but I think we can simplify what's happened a bit. Three points sum up the Bushwacked economy: 1) there has been a major transfer of wealth to the rich, who increasingly are non-Americans -- e.g., weakened labor, oil prices, tax shifts, trade deficits, sinking dollar; 2) there has been major increases in risk, starting with massive growth both of public and private debt; 3) in the long term we will come to see huge opportunity costs as Bush has spent money for the wrong things, starting with the ruinous Global War on Terror. Another thing to look into is how these effects have been masked, which has thus far largely kept them out of sight and mind. The longer tensions go unnoticed in geologic faults, the more severe the eventual earthquake becomes.

Tony Karon: The Problem in Pakistan. The Bush administration is still trying to fix up its mess in Pakistan, but most of its problems are of its own making:

But what's missing in most of the media reports is a clear sense of why Musharraf is unpopular. It's not because of his emergency rule, or because he has denied power to the established politicians who represent a feudal elite comprised of 22 families (including Bhutto's) who own 60% of the land in Pakistan -- many of the reports coming from Pakistan's cities suggest that the majority of the population remains largely unmoved by the showdown between Musharraf and the political opposition.

No, the most important reason for Musharraf's poor standing in the eyes of his population -- as the Washington Post has finally let on -- is because of his willingness to support the U.S. "war on terror." As the post reported it, "Musharraf and the troops he commands have lost support among many Pakistanis. The president has been criticized for undermining national interests in favor of the Bush administration's in counterterrorism operations. Public approval of the military sank after soldiers launched a deadly raid at a pro-Taliban mosque in Islamabad, with troops facing off against religious students."

Karon also quotes Anatol Lieven:

As far as the Pakistani masses are concerned, however, by far the most important reason for the steep fall in his popularity has been his subservience to the demands of the U.S. in the "war on terror," which most Pakistanis detest.

Karon again: "The bottom line in Pakistan, where all opinion polls find Osama bin Laden an overwhelmingly more popular figure than President Bush, is that even the urban middle class opposes Pakistan's frontline role in fighting the Taliban and al-Qaeda. It is a war that most Pakistanis see as benefiting a hostile U.S. agenda -- even those Pakistanis who want no truck with Shariah law themselves." This goes back to Bush's original imperious diktat: either you're with us or you're against us. It turns out that being "with us" means biting off a lot more than is palatable to anyone outside the GOP focus groups.

This may be a good point to note the elections in Australia, which disposed of Bush GWOT ally John Howard.

Chris Floyd: Killers and Extremists in the Pay of Petraeus. This spells out in more detail what I've suspected about the "improved security" in Iraq. It looks like the troop surge had nothing to do with it. Indeed, as long as more troops contested more territory, US and Iraqi casualties kept rising. Only after the Surge failed Petraeus came up with the scheme to cede Anbar to Sunnis willing to take American dollars and guns and quell al-Qaeda. We've known all along that the Sunni leaders would turn on al-Qaeda as soon as the latter ceased to be useful in attacking the Americans. We've also known that the key to any sort of peace in Iraq is the disengagement of US troops. The converse is no doubt true as well: put US troops in Kurdistan and you'll see violence there too.

Saturday, November 24, 2007

Ira Katznelson: When Affirmative Action Was White Ira Katznelson: When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold

History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America

(2005; paperback, 2006, WW Norton)

Ira Katznelson: When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold

History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America

(2005; paperback, 2006, WW Norton)

I picked out this book after reading Paul Krugman's The Conscience of a Liberal. Krugman's theme is how the New Deal, in response to the Great Depression and World War II, led to a significant degree of income equalization in the US, both lifting many working class people out of poverty and reducing the after-tax income of the very rich. Of course, it didn't always work out like that, and this is another side of the story. Katznelson details how New Deal programs were designed to exclude blacks and how those programs that built a politically significant middle class also had the effect of increasing the economic disparity between whites and blacks. The other piece of this story, which Krugman alludes to and Katznelson describes in more detail without drawing much in the way of conclusions is how white racism, starting with the strategies southern Democrats developed to preserve segregation in face of federal "affirmative action" programs, enabled the conservative Republic ascendency that has dominated Washington from Reagan to Bush, persistently eating away at New Deal and Great Society programs while restoring income inequities to levels not seen since the Gilded Ages. The key event there was the support of southern Democrats for Taft-Hartley, undermining an organized labor movement that threatened to organize low-wage southern blacks, and ultimately damaging the Democratic party by marginalizing its labor supporters. Of course, by then the white southern Democrats had mostly switched to the Republican party.

(pp. 22-23):

The South's representatives built ramparts within the policy initiatives of the New Deal and the Fair Deal to safeguard their region's social organization. They accomplished this aim by making the most of their disproportionate numbers on committees, by their close acquaintance with legislative rules and procedures, and by exploiting the gap between the intensity of their feeling and the relative indifference of their fellow members of Congress.

They used three mechanisms. First, whenever the nature of the legislation permitted, they sought to leave out as many African Americans as they could. They achieved this not by inscribing race into law but by writing provisions that, in Robert Lieberman's language, were racially laden. The most important instances concerned categories of work in which blacks were heavily overrepresented, notably farmworkers and maids. These groups -- constituting more than 60 percent of the black labor force int he 1930s and nearly 75 percent of those who were employed in the South -- were excluded from the legislation that created modern unions, from laws that set minimum wages and regulated the hours of work, and from Social Security until the 1950s.

Second, they successfully insisted that the administration of these and other laws, including assistance to the poor and support for veterans, be placed in the hands of local officials who were deeply hostile to black aspirations. Over and over, the bureaucrats who were handed authority by Congress used their capacity to shield the southern system from challenge and disruption.

Third, they prevented Congress from attaching any sort of anti-discrimination provisions to a wide array of social welfare programs such as community health services, school lunches, and hospital construction grants, indeed all the programs that distributed monies to their region.

As a consequence, at the very moment when a wide array of public policies was providing most white Americans with valuable tools to advance their social welfare -- insure their old age, get good jobs, acquire economic security, build assets, and gain middle-class status -- most black Americans were left behind or left out.

(p. 40):

The South's political leaders thus had to find a tolerable balance between two sources of tension. The region's poverty impelled them to pursue fresh and significant sources of federal help, especially because their states were unable to add much on their own. But they had to keep payments low and racially differentiated so as not to upset their low-wage economy, anger employers, or unsettle race relations. The key decision was an agreement by the southern supporters of the New Deal not to pay relief at a level higher than prevailing local standards. They also secured such accommodations as excluding agricultural workers from relief rolls at planting and harvesting times. Furthermore, they had to manage the strain that potentially might be placed on local practices by investing authority in federal bureaucracies. "With our local policies dictated by Washington," the Charleston News and Courier editorialized in 1934, "we shall not long have the civilization to which we are accustomed." To guard against this outcome, the key mechanism deployed was a separation of the source of funding from decisions about how to spend the new monies.

(p. 57):

An explicit legislative exclusion of agricultural and domestic workers from New Deal labor legislation first appeared in the National Labor Relations Act. To be sure, the original draft of the bill introduced by Senator Wagner contained no such exclusion. In the course of examining a witness in the Senate hearing, Senator David Walsh, a Massachusetts Democrat, observed that as the bill was drafted, "it would permit an organization of employees who work on a farm, and would require the farmer to actually recognize their representatives, and deal with them in the matter of collective bargaining."

This possibility triggered discussion of the issue when the bill was referred to the Committee on Education and Labor. Senators Hugo Black of Alabama, who later would change his views about race and segregation, and Park Trammell of Florida worked closely with three non-southern Democrats representing rural states to report a bill containing the exemption of agricultural and domestic labor in precisely the form that would be included in the final passage of the bill.

(p. 61):

During the Second World War, even this arrangement proved unsettling to the southern wing of the party. Pressed by wartime social change, southern Democrats shifted positions, moving to limit the effect of the labor regime they had helped install. With unemployment eliminated by wartime production, and with many blacks entering the industrial labor force at a time when many white workers were overseas, unions began to organize southern workers, including many blacks. In this context, southern representatives feared that the New Deal rules for labor and work they had helped create would undermine the region's traditional racial order. As a result, they shifted their votes from the pro-labor column to join with Republicans during and after the war to make it more difficult for workers to join unions and to limit their rights at the workplace. The country's system for regulating unions and the labor market took on an even more decidedly racial tilt. Politically, this shift by southern Democrats would radically transform American politics, as well as labor legislation, for decades to come.

(p. 69):

The tight labor market induced by wartime industrial expansion was fueled by large federal investments, by urbanization, and by the substantial development of military bases; this in turn facilitated aggressive union efforts to take advantage of the legal climate that had been created by the Wagner Act but previously had had little effect in the South. In just two years, from Pearl Harbor to late 1943, industrial employment in the South grew from 1.6 million to 2.3 million workers. And many farmers and sharecroppers who experienced military service or worked at war centers were not prepared to tolerate a return to prewar conditions (during the war, one in four farmworkers left the land).

(pp. 77-78):

The changes that the Portal to Portal Act wrought to the FLSA also diminished the ability of organized labor to utilize legal resources to protect workers' rights. The rules it fashioned are an object lesson in the considerable difference that seemingly modest procedural changes to public policy can make. The year 1947, the last before Portal to Portal regulations came into effect, stands out for the high number of enforcement suits filed in federal court (3,772) demanding compliance with the Fair Labor Standards Act, the most in any single year before or since. This peak reflected a steady rise in such judicial interventionism in the labor market under the aegis of FLSA during the prior three years. Once Congress enacted its amendments making such proceedings more difficult, the number of enforcement actions plummeted, in 1948, by 72 percent, to 1,062. During the decade following enactment the average annual number of suits filed was 754, representing a decline of some 80 percent from the high-water mark of 1947. Further, as the overall legal climate for labor altered and FLSA enforcement declined, the cooperation offered by many states in enforcing minimum wages and maximum hours waned, especially in the South.

When the impact of more limited possibilities became clear to the leaders of organized labor, they opted to make three fateful moves, all rational in this new context and all successful in the short term. First, they reined in their once ambitious efforts, focused on the South, to make the labor movement a genuinely national force. This strategy now had become prohibitively costly. Instead, they opted to focus attention where their strength already was considerable. Second, they concentrated on making collective bargaining a settled, orderly, and productive process, trading off management prerogatives for generous, secure wage settlements indexed to inflation. In so doing, they experimented with long-term contracts (such as the UAW-General Motors five-year agreement in 1950), while limiting their scope of attention almost exclusively to the workplace. Third, rather than continue to fight for a more advanced national welfare state for all Americans, they concentrated on securing private pension and health insurance provisions for their members that would be financed mainly by employers.

Under these circumstances, the South's political, social, and economic structure remained largely unchallenged by organized labor, the one national force that had seemed best poised to do so in the 1940s. In consequence, the emerging judicial strategy and mass movement to secure black enfranchisement and challenge Jim Crow developed independently of a labor movement that looked increasingly inward and minimized its priority of incorporating black workers within its ranks. Two effects stand out. First, the incipient civil rights impulse rarely tackled the economic conundrums of southern black society directly, focusing instead mainly on civic and political, rather than economic, inclusion. Second, the unions' potential to alter the status of the majority of black working people profoundly failed to take hold.

(p. 101):

The 1940 Census had revealed that some 10 million Americans had not been schooled past the fourth grade, and that one in eight could not read or write. This, primarily, was a southern problem. A higher proportion of blacks living in the North had completed grade school than whites in the South.

(pp. 101-102):

Thus, in the midst of a war defined in large measure as an epochal battle between liberal democracy and Nazi and Fascist totalitarianism, one that distinguished between people on the basis of blood and race, the U.S. military not only engaged in sorting Americans by race but in policing the boundary separating white from black. Because the draft selected individuals to fill quotas to meet the test of a racially proportionate military and because they were assigned to units based on a simple dual racial system,the notion of selective service extended to the assignment of definitive racial tags. The Selective Service system soon found this often was not a simple task. The issue of classification proved particularly vexing in Puerto Rico, where the population was so various racially and where the island's National Guard units had been integrated. Even here, registrants were sorted by race and the National Guard was divided into two sections. The large number of mixed race individuals in the border states, the Creole population of Louisiana, and American Indians offered other challenges, as did ambiguous individual cases almost everywhere. Embarrassingly, the Selective Service fell on blood percentages, using racial guidelines not unlike the country's European enemy, Nazi Germany. Ordinarily, the rule it used was "that 25 percent Negro blood made a person a Negro." Nonetheless, Hershey made clear that it would be unwise for the local board to disrupt "the mode of life which has become so well established" when a draftee in question had been passing as white. After August 1944, the system was sufficiently overwhelmed that he took the decision, at first resisted by Secretary Stimson, to accept the classification an individual claimed for himself when a dispute over racial assignment came to pass.

(pp. 102-103):

For Jews, in particular, the Second World War produced a shift in standing that was quite radical. On its eve, "Jews were not so confident of their prospects in America." During the period of economic hardship, resurgent anti-Semitism, and grim news from Palestine and above all from the heartland of Europe in the 1930s, American Jews faced quotas on admission to leading universities, markedly to professional schools, and a more widespread restrictive system of anti-Semitic practices that impelled the creation of parallel networks of hotels, country clubs, and other social institutions. Before the First World War, most Jews had not sought to enter crowded labor markets outside their areas of economic specialization, notably in the garment trades. But in the interwar period, as the children of immigrants sought to move beyond these niches, they discovered high walls barring many types of employment, in particular in banking, insurance, and engineering. Public opinion polls revealed a great deal of skepticism and many popular myths about Jews. Anti-Jewish expression often was unguarded and unashamed. Enhanced Jewish visibility in economic and civic life often went hand in hand with heightened apprehension and nervous efforts to limits Jewish prominence, as in the case of the unsuccessful effort in 1938 by the Jewish secretary of the treasury and the Jewish publisher of the New York Times to persuade President Roosevelt not to appoint a second Jew to the Supreme Court.

In contrast, by the 1950s, Jewish Americans had achieved remarkable social mobility, high measures of participation in American life, and impressive political incorporation. Anti-Semitism had become unfashionable, at least its open expression. University barriers to entry became more permeable. Mobility from one generation to the next accelerated as access to formerly closed occupations quickened. Housing choices multiplied. Jews entered mass culture on vastly more favorable terms. The war, in short, proved a great engine of group integration and incorporation. Under arms, American Jews became citizens in a full sense at just the moment that Jews virtually everywhere in Europe were being extruded from citizenship. Jews served as officers in the U.S. military as well as enlisted men in higher proportions than their share of the population. After the First World War, they often were classified with blacks as a racial minority. By the 1940s, they were linked with predominantly Catholic groups to compose the category of white ethnics -- a grouping that signified the extension of American pluralism and tolerance.

(pp. 108-109):

The decision to take and educate these individuals with marginal education was the result primarily of immense pressures from the field for more soldiers, but it also had another source. Across the South, white leaders, including some of its most vociferous racists like Mississippi's Senator Bilbo, were insisting that black men be removed from communities from which so many white men were absent but white women were still present. "In my state," he told a Senate committee in the fall 1942, "with a population one-half Negro and one half white . . . the system that you are using has resulted in taking all the whites to meet the quota and leaving the great majority of Negroes at home." In these circumstances, he advised the Department of War: "I [am] anxious that you develop the reservoir of the illiterate class . . . so that there would be an equal distribution." Leading civil rights advocates promoted this view because they were keen to reverse the policy that had kept so many blacks who wished to serve out of the military.

The Army's response was to create a massive crash schooling program of Special Training Units. At the military reception centers, organized into segregated classrooms, two out of every three of their students were black. Once in place starting in June 1943, more than 300,000 inductees passed through this program. Half came from the Fourth Service Command that recruited in the deep South. A high proportion, 11 percent, of the new white recruits were classified as illiterate, but fully 45 percent of the black newcomers lacked basic reading skills. Schooling lasted twelve weeks. "Specially prepared textbooks, such as The Army Reader, describing in simple words a day with Private Pete, were used. Bootie Mack, a sailor, enlivened the pages of The Navy Reader" The level of training was modest (the ability tow rite letters, read signs, use a clock, deploy basic arithmetic), but remarkably the great majority, some 250,000, were lifted out of illiteracy in this brief period. Of the black members of these Special Training Units in the first six months of operation, fully 90 percent were assigned to regular units at the conclusion of their schooling, a higher proportion than the 85 percent of whites.

(p. 134):

The gap in educational attainment between blacks and whites widened rather than closed. Of veterans born between 1923 and 1928, 28 per cent of whites but only 12 percent of blacks enrolled in college-level programs. Furthermore, blacks spent fewer months than whites in GI Bill schooling. The most careful and sophisticated recent study of the impact of the bill's educational provisions demonstrated no difference in attendance or attainment that set apart southern from non-southern whites. All on average gained quite a lot. But for blacks, the analysis revealed a marked difference between the small minority in northern colleges and those students who attended educational institutions in the South. For the latter group, GI Bill higher education had little effect on their educational attainment or their life prospects. White incomes tended to increase quite a bit more than black earnings as a result of gaining an advanced education. As a result, the authors concluded, at the collegiate level, "the G.I. Bill exacerbated rather than narrowed the economic and educational differences between blacks and whites."

(pp. 142-143):

But most blacks were left out. The damage to racial equity caused by each program was immense. Taken together, the effects of these public laws were devastating. Social Security, from which the majority of blacks were excluded until well into the 1950s, quickly became the country's most important social legislation. The labor laws of the New Deal and Fair Deal created a framework of protection for tens of millions of workers who secured minimum wages, maximum hours, and the right to join industrial as well as craft unions. African Americans who worked on the land or as domestics, the great majority, lacked these protections. When unions made inroads in the South, where most blacks lived, moreover, Congress changed the rules of the game to make organizing much more difficult. Perhaps most surprising and most important, the treatment of veterans after the war, despite the universal eligibility for the benefits offered by the GI Bill, perpetuated the blatant racism that had marked military affairs during the war itself. At no other time in American history have so much money and so many resources been put at the service of the generation completing education, entering the workforce, and forming families. Yet comparatively little of this largesse was available to black veterans. With these policies, the Gordian knot binding race to class tightened.

(p. 145):

As part of the quest for civil rights in the Kennedy years, affirmative action did not yet connote compensatory treatment or special preferences. Rather, it simply implied positive deeds to combat racial discrimination. Yet even int he early 1960s the idiom of affirmation suggested more far-reaching possibilities. From the start of the decade, Johnson seemed to understand what he would later say aloud at Howard. Civil rights alone would not be sufficient. The growing gap between white and black Americans demanded more. When Johnson was designated in early 1961 to chair the Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, he privately advised the president that the Eisenhower administration's non-discrimination clause for governmental contracts should "be revised to impose not merely the negative obligation of avoiding discrimination but the affirmative duty to employ applicants.

(p. 147):

The Nixon administration, far from opposing these new measures, expanded the policy by further applying the doctrine of "disparate impact" (rather than "disparate treatment"). Seeking to embarrass organized labor, and enlarge a growing schism between the civil rights movement and white members of unions who might be persuaded to shift their votes to the Republican Party, Nixon enforced the Philadelphia Plan first drafted by Johnson's Department of Labor in 1967, which required that minority workers in the notoriously discriminatory construction trades be hired in rough proportion to their per centage in the local labor force. Soon, one or another form of the Philadelphia Plan -- a plan Nixon called "that little extra start" -- was adopted in fifty-five cities. When the U.S. Comptroller General argued that this program violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, Attorney General John Mitchell rejoined that the "obligation of nondiscrimination" entails taking into account the racial implications of "outwardly neutral criteria" that might, nonetheless, produce deeply unequal outcomes by race.

(p. 164):

The consequences proved profound. By 1984, when GI Bill mortgages had mainly matured, the median white household had a net worth of $39,135; the comparable figure for black households was only $3,397, or just 9 percent of the white holdings. Most of this difference was accounted for by the absence of homeownership. Nearly seven in ten whites owned homes worth an average of $52,000. By comparison, only four in ten blacks were homeowners, and their houses had an average value of less than $30,000. African Americans who were not homeowners possessed virtually no wealth at all.

(pp. 168-169):

Curiously, a series of forgotten early experiments in affirmative action by the military just after the Second World War can help point the way. Affirmative action for blacks began well before the term existed. With millions of soldiers coming home but security needs still pressing, the Department of War conducted a sober assessment of the campaigns in Europe, North Africa, and Asia. The way race had been handled, it concluded, had diminished the fighting capability of the armed forces. Responding to the study, the military decided to raise the educational level of black troops to improve their readiness and create a deeper pool from which to recruit black officers. The Far East Command established such a program, aimed principally at blacks, to bring every soldier to a fifth-grade standard. Elsewhere, race was used more explicitly to define eligibility. At Georgia's Fort Benning, the Army initiated an educational program for members of the all-black 25th Combat Regiment who had secured less than an eighth-grade education. But the most far-reaching program took place in occupied Germany. Starting in 1947, thousands of black soldiers undergoing basic military training at the Grafenwohr Training Center received daily instruction for three months in academic subjects up to the level of the twelfth grade.

Soon, the training center moved to larger quarters at Mannheim Koafestal. By the close of the year, the results had been so positive that a larger, remarkably comprehensive program exclusively for black soldiers was launched at Germany's Kitzingen Air Base. All African American troops arriving from the United States passed through the program. Black units stationed in Europe were required to rotate through Kitzingen for refresher courses. Once this on-site instruction was completed, Army instructors traveled with the soldiers to continue their schooling in the field. The participants were required to stick with the course until they reached a high school equivalency level or demonstrated they could make no further gains. By 1950, two thirds of the 2,900 black soldiers in Europe were enrolled.

Military affirmative action worked. These men made striking advances in Army classification tests. That year, the European Command estimated that the program "was producing some of the finest trained black troops in the Army." Soon, the number of qualified black officers increased considerably. Breaking with the masked white affirmative action of the 1930s and 1940s, race counted positively and explicitly to improve the circumstances of African Americans.

(p. 170):

Beneficiaries must be targeted with clarity and care. The colorblind critique argues that race, as a group category, is morally unacceptable even when it is used to counter discrimination. But this view misses an important distinction. African American individuals have been discriminated against because they were black, and for no other reason. Obviously, this violates basic norms of fairness. Under affirmative action, they are compensated not for being black but only because they were subject to unfair treatment at an earlier moment because they were black. If, for others, the policies also were unjust, they, too, must be included in the remedies. When national policy kept out farmworkers and maids, the injury was not limited to African Americans. Nor should the remedy be.

Friday, November 23, 2007

Juan Cole: Napoleon's Egypt

Juan Cole: Napoleon's Egypt: Invading the Middle East (2007,

Palgrave Macmillan)

Juan Cole: Napoleon's Egypt: Invading the Middle East (2007,

Palgrave Macmillan)

Juan Cole is a professor of history at the University of Michigan, specializing in the political history of Shi'ism in the Middle East, especially Iraq. Over the last few years he has written a prolific blog called "Informed Comment" which focuses mostly on Bush's Iraq War debacle, during which time he's established himself as the single most useful source of information on the war. Given this, it might be reasonable to expect him to draw analogies between the latest Western invasion of the Middle East and the first modern (post-Crusades) one, but he shies away from doing so. Actually, the book seems designed to reinforce Cole's credentials as a serious historian. But he did draw some conclusions in a piece at TomDispatch: "This first Western invasion of the Middle East in modern times had ended in serial disasters that Bonaparte would misrepresent to the French public as a series of glorious triumphs." More:

For both Bush and Bonaparte, the genteel diction of liberation, rights, and prosperity served to obscure or justify a major invasion and occupation of a Middle Eastern land, involving the unleashing of slaughter and terror against its people. Military action would leave towns destroyed, families displaced, and countless dead. Given the ongoing carnage in Iraq, President Bush's boast that, with "new tactics and precision weapons, we can achieve military objectives without directing violence against civilians," now seems not just hollow but macabre. The equation of a foreign military occupation with liberty and prosperity is, in the cold light of day, no less bizarre than the promise of war with virtually no civilian casualties.

It is no accident that many of the rhetorical strategies employed by George W. Bush originated with Napoleon Bonaparte, a notorious spinmeister and confidence man. At least Bonaparte looked to the future, seeing clearly the coming breakup of the Ottoman Empire and the likelihood that European Powers would be able to colonize its provinces. Bonaparte's failure in Egypt did not forestall decades of French colonial success in Algeria and Indochina, even if that era of imperial triumph could not, in the end, be sustained in the face of the political and social awakening of the colonized. Bush's neocolonialism, on the other hand, swam against the tide of history, and its failure is all the more criminal for having been so predictable.

A selection of quotes from the book. One similarity between Napoleon in Egypt and Bush in Iraq is that the invading armies were invincible in direct military confrontations, but both were harried from the start by irregular fighters -- in Napoleon's case mostly by Bedouin. Small acts of rebellion were consistent and pervasive, took a slow toll of attrition, and were haphazardly met by brutal repression, which might seem to work but not for long. Both made flamboyant use of propaganda to sway hearts and minds, but both made stupid mistakes in doing so, their efforts ringing hollow. One difference is that the French faced a serious external threat, especially from Britain's dominant naval position. Britain's ability to blockade Egypt made the Egyptians' war of attrition all the more damaging. It also meant that Napoleon had to fend for himself in Egypt, which made his occupation much more predatory. By contrast, Bush is able to pump huge amounts of money into Iraq -- a drain which hurts public opinion in the US, but which makes the occupation much more self-sustaining.

(pp. 12-14):

The genesis of Bonaparte's plan to invade Egypt is complex. A few French intellectuals and merchants had entertained the idea of such a project over the previous century, given the indisputable centrality of Egypt to French commerce in the Mediterranean and points east. Bonaparte himself appears to have begun seriously considering it in the summer of 1797 as a result of his Italian campaign. The principalities of Italy bordering the Adriatic Sea had long had interets in Adriatic islands and in Croatia and Ottoman Albania. Venice and the Adriatic city of Ragusa provided the leading foreign element among merchant communities in the Egyptian port of Alexandria. And revolutionary France, now established as an Italian power, had more inteests in the Levant than ever before -- something of which Bonaparte, as the virtual viceroy of the Italian territories, would be well aware.

A prominent politician, revolutionary, and former priest, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, had argued just the previous summer in a speech to the National Institute that Republican France needed colonies in order to prosper. (Canada, Louisiana, and many of its Caribbean and Indian possessions had been lost to it decades before.) He rooted this demand in the revolutionary ethos of the new Republic, saying, "The necessary effect of a free Constitution is to tend without cessation to set everything in order, within itself and without, in the interest of the human species." He related that he had been struck, during his brief exile to the United States during the Terror, at how their postrevolutionary situation differed from that of France in lacking intense internal hatreds and conflicts, and he attributed this relative social peace to the way in which settling a vast continent drew the energies of restless former revolutionaries. Talleyrand recalled earlier plans for a French colony in Egypt and pointed to British sugar cultivation in Bengal, implying that such imperial commodity production strengthened this rival and that France should also seek profits through colonial possessions that would produce lucrative cash crops. He also suggested that the days of slavery were numbered, and implied that colonies that generated wealth through slave plantations should be replaced with satellite French-style republics dominated by Paris.

Throughout the 1790s, British naval superiority had confined the expansionist French to the Continent and thwarted any attempt to overthrow the British enemy. Talleyrand argued that a renewed colonialism offered "the advantage of not in any way allowing ourselves to be forestalled by a rival nation, for which every one of our lapses, every one of our delays along these lines is a triumph." The French had lost their toehold in South India at Pondicherry to the British, but were attempting to ally with local anti-British Indian rulers in hopes of expelling the British East India Company from the subcontinent. Taking Egypt would give France control over other valuable commodities, especially sugar, and might provide a means of blocking the growth of a British empire in the East. [ . . . ]

Victorious in Italy, Bonaparte began corresponding with Talleyrand and other leaders about the possibilities of a French Mediterranean policy as a means of hurting the British. On 16 August 1797, he wrote, "The time is not far away that we will feel that, in order truly to destroy England, we must take Egypt. The vast Ottoman Empire, which dies every day, lays an obligation on us to exercise some forethought about the means whereby we can protect our commerce with the Levant." The Old Regime and the early Republic had supported the Ottoman Empire as a way of denying the eastern Mediterranean to its powerful continental rivals. Bonaparte and Talleyrand, in contrast, became convinced that the Ottoman decline was accelerating, producing a dangerous impetus for Britain and Russia to attempt to usurp former Ottoman territories. If the European might soon begin capturing provinces of Sultan Selim III, then Bonaparte and Talleyrand wanted the Republic of France to be the first in line. Excluded by the British navy from the North Atlantic and lacking possessions near the Cape of Good Hope, they dreamed of making the Mediterranean a French lake and of opening a route to India via the Red Sea, and recovering Pondicherry and other French possessions on the Coromandel and Malabar coasts.

(p. 29):

The theme of the degeneration of what had once been the classical world was well established by the eighteenth century, having been elaborated early in the century by French travelers to and writers about Greece. Degeneration allowed the French to appropriate classical civilization for their own, displacing its splendor into the distant past and positioning its present heirs as unworthy, such that the mantle of those glories fell on the French instead. Still, it should be underlined that despite the racist overtones of the phrase, degeneration did not refer, for these Directory-era Frenchmen, to a hereditary condition of the blood. Rather, they believed that the climatic and social conditions of Egypt had produced tyranny and excess, which were amenable to being reversed. This attempt at restoring the Egyptians to greatness and curing their degeneracy through liberty and modernity was central to the rhetoric of the invasion.

(p. 30):

Bonaparte, having secured Alexandria, issued a proclamation setting forth to the Egyptians the reasons for the invasion and what the French government expected from them. The French Orientalist Jean Michel de Venture de Paradis, perhaps with the help of Maltese aides, translated the document into very strange and very bad Arabic. The Maltese, Catholic Christians, speak a dialect of Arabic distantly related to that of North Africa, but they were seldom schooled in writing classical Arabic, which differs with regard to grammar, vocabulary, and idiom from the various spoken forms. Venture de Paradis, who had lived in Tunis, knew Arabic grammar and vocabulary but not how to use them idiomatically. The French thus first appeared to the small elite of literate Egyptians through the filter of a barbarous accent and writing style, making them seem rather ridiculous, despite Bonaparte's imperial pretensions. It would be rather as though they had conquered England and sent forth their first proclamation in Cockney. But ungrammaticality and awkward wording were not the worst of the statement's difficulties. Much of it simply could not be understood by most Egyptians, since it sought to express concepts for which there were no Arabic equivalents.

(p. 45):

As they approached Rahmaniya, the troops finally neared the sweet water of the Nile, though for strangers in unfamiliar territory its charms were attended with danger. The grenadier François Vigo-Roussillon recalled, "The entire army -- men, horses and donkeys -- threw themselves into that sought-after river. How delicious these healthful waters seemed to us! Nevertheless, many men were mutilated or carried away by crocodiles." He said that his unit proceeded up the left bank for about a league, then bivouacked in squares (no doubt keeping as much an eye out for the crocs as for enemy soldiers).

(pp. 54-55):

In the 1600s and 1700s Egypt emerged as the center of a vast and lucrative coffee trade. Coffee trees probably came to Yemen from Ethiopia, and in the 1500s the people of Cairo first learned that brewing the beans and drinking the hot juice had become popular in Sanaa, especially among Sufi mystics seeking to stay up late for prayer and meditation. By the 1600s, the custom of coffee-drinking had spread beyond the mystics to the general public, and coffeehouses opened all over the Ottoman Empire, often to the dismay of authoritarian sultans and governors who feared them as places where sedition might brew in heated conversations as easily as a thick mocha blend. Ottoman attempts to ban coffee or coffeehouses, however, failed miserably. In the mid-to-late 1600s, a few coffeehouses began to be opened in Europe. European monarchs initially dreaded them as much as had the sultans. The first was founded in Paris in 1671. The Café Le Procope, set up in the French capital in 1689, later became a center for intellectual discussion and revolutionary ideas. Cairo was among the major entrepôts for marketing coffee in the Ottoman Empire and to Europe. It is tempting to observe in jest that, if indeed the rise of the coffeehouse had anything to do with the coming of the French Revolution, it may be that Egyptian coffee merchants inadvertently set in train the caffeinated, fevered discussions that overthrew the Old Regime and ultimately sent a French fleet on its way to Alexandria.

Some more general background on the Mamluks and Ottomans (pp. 53-56):

Egypt was a largely Arabic-speaking society, but it was at that time [1798] under the nominal rule of the Ottoman Empire, with its capital in Istanbul (which had been Constantinople under the Romans and Byzantines). When the Ottomans conquered Egyptin 1517, they displaced a ruling caste of slave soldiers called the Mamluks, most of them initially Christian youths from Circassia in the Caucasus, where they were taken as slaves when defeated on local battlegrounds. Medieval Muslim rulers often feared that if they depended too heavily on local tribal warriors or on an army recruited from a pastoral population with strong clan ties, then these kinship groups would retain their own regional interests and would set the rulers aside in a coup. Rulers had often depended on imported slave soldiers, because slavery is a form of social death in which the individual is cut off from his family and place of origin. Slaves, they thought, would lack such thick networks of kinship and so would be more loyal to the sovereign. They were converted to Islam, and most lost close contact with their families abroad. Mamluks, despite starting as slaves, were often paid very handsomely and had the opportunity to rise high in the military, the bureaucracy, or the court. On reaching adulthood, they were awarded their freedom but remained loyal to their former master. Ironically, barracks full of slave soldiers often established new networks of friendship and professional contacts that allowed them in some instances to make successful revolts against their sultans. The Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt, the most famous member of which was Saladin, the nemesis of the crusaders, maintained a large number of Mamluks. In 1250, when their Ayyubid monarch died, and as Egypt faced a potential onslaught from invading Mongol hordes, the Mamluk soldiers made a military coup and took over the country and then ruled it for themselves for two and a half centuries.

When, on 24 January 1517, Sultan Selim I of the Ottoman Empire swept into Cairo, he reduced it to an appendage of Istanbul. The Ottomans incorporated Egypt into one of the largest empires in the history of the world, a flourishing trade emporium that linked India in the east with Istanbul via Iraq and then Istanbul with Marseilles in the west across the Mediterranean. The empire at its height had thirty-two provinces, of which thirteen were Arabic-speaking, and Egypt, among the more populous and the most agriculturally productive, became its granary. The Ottomans subordinated the Circassian slave soldiers in Egypt to their own bureaucracy and their own system of military slavery. Istanbul famously established seven long-lasting regiments in Egypt. Five of them were cavalry regiments, and two were infantry. These regiments were staffed by a multicultural and polyglot elite, held together only by their loyalty to the sultan and Islam, their mastery of the Ottoman language (an aristocratic, Persian-inflected form of Turkish), and Ottoman military and bureaucratic techniques. They comprised Anatolian Turks, Bosnians, Albanians, converted Jews, Armenians, Georgians, and Circassians. Within the military, a strong divide existed between those soldiers originally recruited as slaves, who remained at the top of the hierarchy, and the free volunteers from the poor villages of Anatolia. [ . . . ]

During the 18th century, the Georgian houses of slave soldiers in Egypt grew in importance, proving able to subordinate the seven Ottoman regiments and establishing control over the lucrative coffee trade. An Ottoman-Egyptian slave soldier, Ali Bey al-Kabir, rebelled in the 1760s and 1770s, attempting to undermine the sultan's authority by asserting power in the Red Sea and opening it to European commerce, as well as by invading Syria. His rebellion ended, but after a while the beys of Cairo again ceased paying tribute to the Ottoman sultan, provoking an Ottoman invasion in 1786 that halted the province's slide toward autonomy. Although in earlier decades we historians tended to write off the eighteenth century as a time of the resurgence of Mamluk government in Egypt, as though the old state of the 1200s through the 1400s had been revived, we now know that this way of speaking is inaccurate. The Ottomans had endowed Egypt, however, independent it sometimes became, with their own institutions, including their distinctive form of slave soldiery. For this reason, it is more accurate to call the eighteenth-century ruling elite "Ottoman Egyptians." Arabic chronicles of the time often called them "ghuz," a reference to the Oghuz Turkic tribe, which also implied that they were best seen as Ottomans (a Turkic dynasty). Most gained fluency in both Ottoman Turkish and Arabic, while retaining their knowledge of Caucasian languages such as Georgian and Circassian. Not all of the emirs had a slave-soldier background, and some were Arabic-speaking Egyptians.

The eighteenth century was not kind to Egypt. Between 1740 and 1798, Egyptian society went into a tailspin, its economy generally bad; droughts were prolonged, the Nile floods low, and outbreaks of plague and other diseases frequent. The slave-soldier houses fought fierce and constant battles with one another, and consequently raised urban taxes to levels that produced misery. Now a new catastrophe had struck, in the form of Bonaparte's plans to bestow liberty on Egypt.

(pp. 93-96):

As Ibrahim Bey disappeared into the sands of the Sinai, his departure drew a curtain over nearly a quarter century of Egyptian history. He, along with his partner Murad Bey, had ruled Egypt since the mid-1770s. Now he fled east even as Murad headed south, their palatial mansions suddenly become the homes of foreign officers, their wives taxpayers to the Republic of France or mistresses to her generals, their entourages and slave soldiers scattered, killed, or suborned to new loyalties. [ . . . ]

Ibrahim Bey had been in the political wilderness before and survived to return to power. Mehmet Ebu Zahab, who had been Ibrahim's owner, died in 1775 while campaigning in Syria on behalf of the Ottoman sultan to repress a rebellious sheikh of the Galilee at Acre. In the subsequent decade, Ibrahim and Murad established themselves as the paramoutn beys in Egypt. The Georgian Mamluks retained ties to their homeland, which was increasingly in St. Petersburg's sphere of influence as Russia expanded into the Caucasus, and they began to explore a Russian alliance. Facing difficulties in recruiting enough Mamluks to replenish their ranks, the Mamluk leaders even brought in a brigade of five hundred Russian troops in 1786. In the early 1780s, the Ottoman government, or Sublime Porte, became concerned about the loyalty of the Qazdaghlis, and in a 1783 communiqué to the governor os Syria, it warned him that the dalliance of these "tumultuous beys" with Russia could prove injurious to the empire. [ . . . ]

In July 1786, the Ottoman commodore Hasan Pasha, arrived in Alexandria with a small contingent of troops. After his envoy conducted inconclusive negotiations with Ibrahim Bey, he marched on Rosetta. He sent couriers to the villages of the Delta announcing that the Ottoman sultan had decided to much reduce their taxes.

Hasan Pasha was able to take Cairo and restore Ottoman power, but only temporarily (pp. 99-100):

In August 1786, Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey had headed to Upper Egypt, where they drew to themselves a remnant of the beys and made alliances with the local Bedouin. An expedition south by the commodore, aimed at decisively defeating them, faltered in the fall when the imperial troops lost their cannon in battle with the rebels and had to retreat to the safety of Cairo. Hasan Pasha left Egypt in 1787 as the prospect of a new Ottoman war with Russia built. Before he departed, he pardoned Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey but stipulated that they should remain in Upper Egypt. By 1791, the attention of Istanbul had turned elsewhere. In that year, an outbreak of plague in Cairo carried off members of the ruling elite as well as their supporters among the commoners and much weakened the fabric of urban society.

Plagues are urban phenomena. They are spread in conditions of urban crowding and carried by such vectors as fleas that infest rats. The clean, harsh desert and the thin population of pastoral nomads preserve them from outbreaks. One implication of this different susceptibility to epidemics in Middle Eastern societies is that the cycle of plagues weakened cities and opened them to periodic Bedouin conquest. Ibrahim Bey, Murad Bey, and their troops and Bedouin allies in Upper Egypt were left unscathed by the epidemic, while the leading pro-Ottoman bey in charge of the country was killed. They were able to march at full strength back into Cairo, reestablishing their beylicate and returning to their old ways, taxing French and other merchants into penury and defying Sultan Selim III's demand for tribute.

(p. 112):

Among Bonaparte's chief difficulties in attempting to rule Egypt was his lack of legitimacy: he was a foreign general of European, Catholic Christian extraction. Many Egyptians feared he would constrain them to convert. The biologist Saint-hilaire wrote that August, "The women are much more afraid. They never stop weeping and crying that we will force them to change their religion." Medieval Islamic law and traditions taught Muslims that they should attempt to avoid living under the rule of non-Muslims if at all possible, even if it meant emigrating. Some jurists did allow an exception where the non-Muslim ruler was not hostile to Islam and allowed the religion freely to be practiced. This loophole was Bonaparte's one chance, and he pursued it as though he were a shyster lawyer with a make-or-break case.

(pp. 120-121):

On 9 August at 8:00 A.M. an armed crowd gathered to attack the French post [in Mansura]. The insurgents were said to number 4,000 men. The soldiers retreated to their barracks, but the crowd pursued them there. They tried to set fire to the barracks, but were driven off by French musket fire. Then the troops began running low on cartridges. They decided they would eventually be overrun if they remained in the barracks, and so they charged out, losing several men to the townsmen's musket balls. They attempted to board some boats on the Nile, but villagers on the other bank began firing at them, killing some and driving away the rest. They therefore headed south, toward Cairo, facing attrition as they weathered further sniping on the way. Reduced to a band of thirty, they had to abandon their wounded, whom the villagers immediately dispatched. Out of ammunition, they finally were set upon by their pursuers and decapitated. One survivor escaped and was given refuge in the village of Shubra, where he was later picked up by a French officer. Another, a French woman accompanying her husband, was captured and married off to an Abu Qawra Arab sheikh.

That night in Damietta, General Vial tried to send some troops southwest to Mansura on the Nile, but they found their path blocked by an armed village allied with some Bedouin, and were forced to abandon their skiffs and return by land to their Mediterranean port. They lost a man killed and six wounded, according to Capt. Pierre-François Gerbaud. Niello Sargy, who was at Rosetta, reported the Mansura rebellion as a Bedouin attack. The careful report submitted by Lieutenant Colonel Théviotte, apparently gleaned from the surviving male eyewitness, does not actually mention Bedouin, and in light of Turk's comments, it is likely that a mixture of townspeople and the Bedouin and peasants who had arrived for market day participated in the uprising.

(p. 157):

Defense of the Muslim community against attack was considered in classical Islamic law a "group obligation." That is, not every single member of the community had an individual duty to fight. When and how to fight was a decision that could not be made by vigilantes, but had to be made by the duly constituted authorities, in this case the sultan. The laws governing holy war, or jihad, required a public declaration of war, a warning to the enemy forces that they would be attacked, the provision of an opportunity for conversion to Islam by the enemy (thus obviating the need for a war), and Muslim adherence to a code of conduct that forbade the killing of noncombatants or women and children. Selim III, by declaring defensive war, said it had now become an individual duty to fight the French, and he thereby authorized guerrilla action by Egyptian subjects. Nothing could have been more dangerous to the French. He combined Islamic and international law by both invoking the duty of defensive jihad and and simultaneously citing international norms of state behavior. How little the sultan viewed the conflict as a clash of civilizations is demonstrated by his immediate alliance with Russia and Britain, Christian powers, against the secular republic he had once befriended.

(p. 172):

These officers saw no contradiction between the demands of force and the enjoyment of liberty. After all, their political achievement had come about through revolution, which is to say through violence. Otherwise the Old Regime would never have been overthrown, or it would have managed to reassert itself. Clearly, "liberty" could not be an entirely voluntary affair in late Ottoman Egypt. It had to be imposed and bolstered by a free metropole. The intertwining of reason, nation, liberty, and terror was an important discourse in the period after the execution of the king, and despite the end of the Terror, this coupling of the Enlightenment to violence continued among some Directory-era thinkers in the context of the wars against Austria, in Italy and Germany, and the need to fight the external enemies of the Revolution. Therefore, the devotees of liberty and reason in Egypt would not have disagreed substantially with Robespierre's dictum, that terror is merely an aspect of justice, delivered swiftly and inflexibly, so that it is actually a virtue, or with his instruction to "break the enemies of liberty with terror, and you will be justified as founders of the Republic." Thus, when Julien, an aide-de-camp of the general, and fifteen Frenchmen who navigated the Nile were killed in August by the inhabitants of the village of Alkam, Say remarked, "The General, severe as he was just, ordained that this village be burned. This order was executed with all possible rigor. It was necessary to prevent such crimes by the bridle of terror."

Faced with continued Egyptian resistance to the occupation, Say acknowledged the necessity of accustoming "these fanatical inhabitants" to the "domination" of "those whom they call infidels." He again admitted French domination, but he hoped that Egyptians could be taught to love it. He concluded, "We must believe that a Government that guarantees to each liberty and equality, as well as the well-being that naturally follows from it, will insensibly lead to this desirable revolution." The revolution alluded to here is not a political event but the spiritual overthrow of an Old Regime of Ottoman-Egyptian dominance and religious "fanaticism." It is this revolution of ideals that so requires the arts as its propagandists, insofar as they are held to speak to the heart as well as the mind.

(pp. 174-175):

The French employed public celebrations and spectacle both to commemorate Republican values and to instill a sense of unity with regard to revolutionary victories. Such "festivals reminded participants that they were the mythic heroes of their own revolutionary epic." The universal wearing of the cockade, the flying of the tricolor, the intricate symbology of columns and banners, the impressive military parades and cannonades, all were intended to invoke fervor for the Revolution and the remaking of society as republic. That some of the French appear seriously to have expected the conquered Egyptians to join them in these festivities demonstrates how little they could conceive of their own enterprise on the Nile as a colonial venture. The greatest use of Republican ideology appears to have been precisely to hide that fact from themselves.

A major revolt broke out in Cairo in October 1798, which the French at last put down brutally (pp. 210-211):